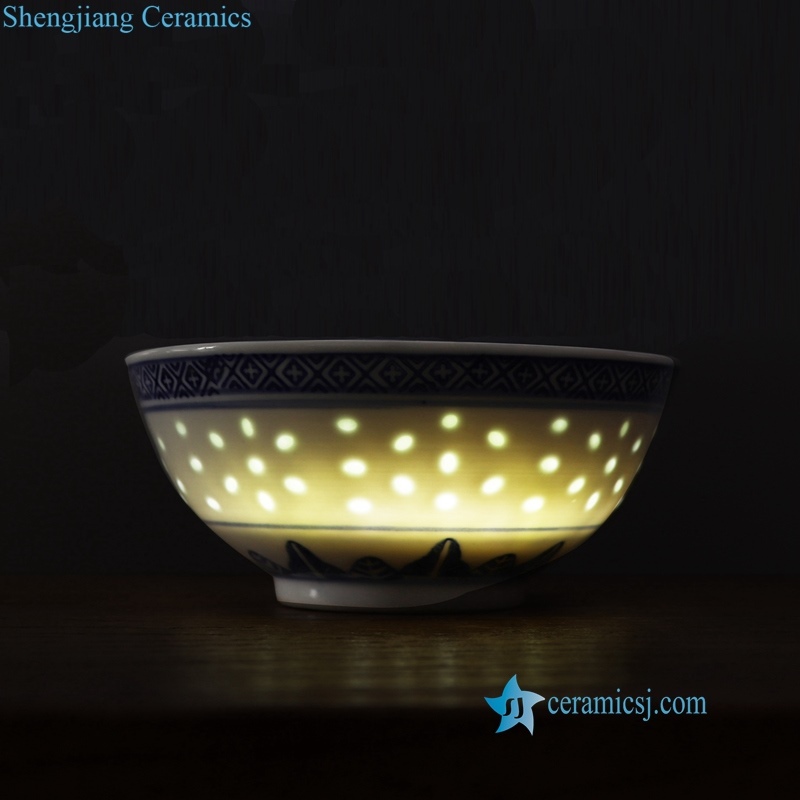

Blue and White Barbed Rim Dish, Yuan Dynasty, 14th Century, sought by the St. Louis Art Museum and purchased last month by London art dealer Guiseppe Eskanazi for $4.2 million

ST. LOUIS • Curators at the St. Louis Art Museum had their hearts set on a 650-year-old porcelain dish from China’s Yuan Dynasty.

They inspected its hand-painted, hair-thin swirls of blue under ultraviolet light at a New York auction house. They deemed it “spectacular” and asked the museum’s board to set aside $1.2 million for its purchase.

But when the auction started last month, the curators realized in the first few minutes that they weren’t even in the running.

The blue-and-white dish, its value listed by the auction house at $200,000 to $300,000, sold for $4.2 million.

“Chinese porcelain is hot stuff — very, very hot,” said Philip Hu, associate curator of Asian art at the museum. “It’s one of the hottest art commodities in the world, of any kind. Within less than 30 seconds, our chances evaporated.”

The market for Chinese ceramics has boomed for the past few decades, fueled by China’s rapid economic growth and new crust of ultra-rich. Chinese businessmen, with money to spare, seek out hand-made porcelain tea cups, dishes and vessels commissioned by centuries of Chinese emperors. They hope not only to expand their own collections, but also to repatriate imperial pottery after years in foreign hands.

Even when Western investors win at auction, they’re often buying to sell, eventually, back to the Chinese.

“The auction house’s assumption is that practically everything is going back to China,” said Patricia Graham, a certified appraiser and researcher at the University of Kansas. “Because they’re the ones with the big money these days.”

It’s a tension that’s long existed between private collectors, many chasing a hot investment, and museum curators, who want to secure works for public display. As collectors clamor for a trendy buy, they drive up prices. Museums that arrive late to the trend are outbid.

In the late 1980s, it was newly wealthy Japanese driving sky-high the cost of Impressionist and Modernist paintings. A decade later, American collectors paid so much for colonial furniture, it became nearly inaccessible, curators say. And in the 2000s, Russian tycoons shelled out millions of dollars for, among other things, the lavish Easter eggs created by artist and goldsmith Peter Carl Fabergé for the Russian Imperial family.

“You can understand, if you’ve made a ton of money, having something on your desk that used to be owned by an emperor makes you feel a little bit like an emperor,” said Marion Maneker, publisher of the Art Market Monitor, an industry blog and newsletter.

“Now that the Chinese have money, they’ve been going around the world and literally hoovering up objects that have value,” Maneker said.

The market peaked earlier this month, when a Shanghai billionaire bought a tiny 3-inch-in-diameter, 500-year-old “Chicken Cup” for $36 million at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, a new record for fine Chinese porcelain.

But Hu, the St. Louis Art Museum’s associate curator, thought the Yuan blue-and-white dish on auction last month at Sotheby’s New York could have been an exception.

He first saw the piece when a March auction catalog — written in English and Chinese — landed on his desk. It was the cover photo.

The piece was rare, exquisite, and filled a hole in the museum’s collection. They had some money to spend — about $1.2 million left from the sale of less valuable pieces.

And Hu thought the museum had a chance at auction. The dish was very blue. Too blue, he estimated, for traditional Chinese tastes.

The Chinese, Hu explained, made two kinds of blue-and-white porcelain during the Yuan Dynasty. Some — often dishes with dense designs in blue — were made as diplomatic gifts or for exportation to what is now Turkey, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Dishes with more of the white porcelain showing were saved for the imperial family and nobility.

The nouveau riche in China see themselves as “latter-day emperors,” Hu said. He figured they might stay away from the bluer pieces.

The museum sent a team of three to the auction: Hu, Deputy Director Jason Busch and board member Mark Weil, chairman of the museum’s collections committee.

On March 18, the day of the sale, Hu carefully picked an auction paddle. He met a New York art dealer, who would bid for the museum, at a restaurant several blocks from the art house. He discreetly passed paddle No. 1128 (a lucky number) to the dealer. They ate lunch — miso soup, gyoza, tempura, sushi — “then we took two separate routes to Sotheby’s.”

Bidding started at $150,000. It rose first in $50,000 increments, then by $100,000.

Within two minutes, Hu said, the price had crested the art museum’s budget.

In the end, the buyer wasn’t a Chinese businessman, but London art dealer Giuseppe Eskanazi, one of the world’s most respected and prolific buyers of Asian art.

The Yuan dish was an investment, Eskanazi said, a “one-of-a-kind” piece to be sold in five or 10 years to an ultra-high-end collector or, perhaps, one of the new private or state-run museums budding across China.

And that means two things, said Graham, the Kansas appraiser:

Chinese buyers are getting more sophisticated. And they’re pricing American museums out of the market.